A benediction to start. I suspect I’ve lifted some of lines out of this poem and seeded them in songs here and there. Incidentally, one of the great songs of reggae’s roots era is Gregory Isaac’s “Babylon Too Rough.” Always a story behind the story behind the story.

When I was 18 years old, my friends and I bought a 1980 gold Chevy Vandura, a cargo model without windows, in Goleta, California. When we went to test drive it, we stayed out too long—we had no idea how long one should test drive anything—and the cops came and found us and told us we needed to bring the van back to seller, a local florist. They thought we were just joyriding. We were very green. We paid $500.

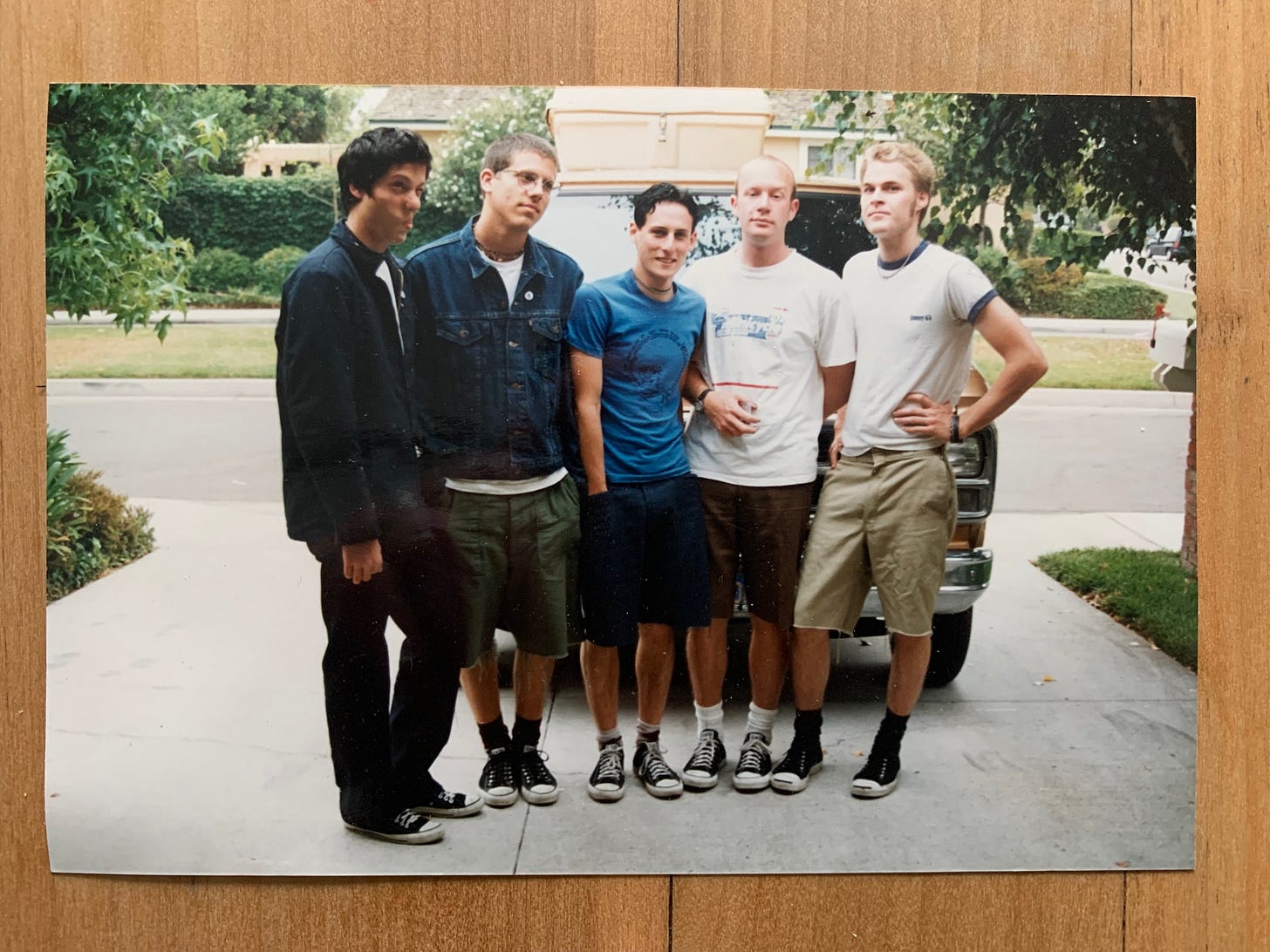

I sometimes wonder whether, had that van broken down somewhere before we'd even crossed any state lines, my life today would be any different. As it turned out, the Chevy Vandura that we named “Goldar” ran more or less like a top. We built a loft bed in the cargo area under which drums and amps could be stored, and drove east out of Southern California. The five of us, plus our roadie and merch seller (and my childhood friend) Ryan, were a band called Ex-Ignota, with two 7” records to our name. I had $200 dollars cash in my pocket, and we were gone for the entire summer, 10,000 miles worth of driving. It was 1994.

Back then—at least in the musical world I existed in—you booked tours yourself through a network of punk kids all over the country to whom you wrote letters and made long-distance phone calls. There was no internet, no cell phones, and no booking agents. If calling long-distance was too expensive on your home line, you procured a dialer, an illegal device that, when held up to the receiver of a payphone, emitted a tone that tricked the phone company into connecting the call free-of-charge. The science of it is a little beyond me, but every punk band worth their salt owned a dialer, and plenty of postcards and stamps.

There were cells of punks in Oakland; Lawrence, KS; Washington, D.C.; El Paso, TX; Ypsilanti, MI; Jersey City; Philadelphia. We were everywhere, hidden in plain sight, and we were booking shows at all-ages VFW halls, recording records, making art and films and 'zines that memorialized our scene. I can't quite convey how beautiful it was, how romantic. Occasionally I meet people even today that were there and we have a shared language, even if I've never met them before. Someone came up to me after a performance in Brooklyn recently and said that he had booked a show for Ex-Ignota; I immediately categorized him in my mind as a lifer, someone that was on the level. I mean, there are a lot of ways to be on the level, but for me, this is one—having witnessed this movement of wandering kids with guitars in the mid-to-late 1990s, having participated in some way in this underground culture and economy that seemed like the only joy available to the lost poetic weirdos that existed on the margins.

I remember the first time I ever played on an actual stage: St Louis, MO. I had already been playing music for a couple years at that point, and I had never been above the audience. We looked at each other and laughed. I remember pulling into a dirt yard in San Antonio, TX, where a punk kid had booked us to play at his sister's quinceanera. The music was totally inappropriate for the occasion, and we set up in his family's laundry room. When we were done his mother gave us $20 and, I kid you not, we thought we were rich. I remember laying in the loft of the van, looking out the back windows as we drove through Upstate New York, amazed at the million different shades of green. When we got to the house where the show was being held, everyone was waiting for us on the porch, the whole crowd, and they all helped us load our gear in. I remember playing a show at a house in Detroit with Dystopia—a truly incredible band that was tangentially connected to our scene—during which a punk kid stumbled into the house in the middle of the show, white with shock, saying that he'd just been body cavity searched by the police.

This is where I first recognized my heart as renegade. As wandering. That I'm writing this 30 years later from a hotel room—still traveling for music, for poetry, to watch the signposts flying by, to keep running—boggles the mind. Like, I can't even square it at this particular moment other to say: I'm still here. I'm still here.

The few things I want to share on this week's installment of A Place Where No One Can Find Me include a mix called In the October Country with Hiss Golden Messenger that is full of tunes that evoke something spooky. I would say this kind of music is maybe a subset of autumn music—maybe more atmospheric? A touch more dread? I don't know, you tell me. The great Carroll Cloar made the painting that graces the digital cover and I borrowed it.

Also, there is a recent recording from a few nights ago in Ridgefield, CT of Rich Hinman and I playing Tim Hardin's “Shiloh Town.” We started playing “Shiloh Town” as an icebreaker at these Bad Debt shows, something to open up the room, before getting down to the existential brass tacks of the entire Bad Debt album. I can't really say enough good things about Rich's playing. I think he's one of the true masters of guitar, and I'm excited to make more music with him.

Below the paywall, there's a long and loping rendition of “No Lord is Free” from Bad Debt that Rich and I played at soundcheck, also in Ridgefield. There's something deep and eerie to it. Talk about spooky—that's a spooky song. Sometimes I recognize myself in it, sometimes I don't. It depends on my mood. Both of these tracks were recorded and mixed by Luc Suer, my deep companion and confidante.